Presented by Esther Menn at the Augustana Adult Forum January 5, 2025

This presentation focuses on the importance of the Magi, also known as the Wise Men or Three Kings, in Christian tradition, primarily by looking at art from early Christianity, the Renaissance, and contemporary times. Then it concludes with reflections on how the Magi might inspire us as Christians living in disorienting and challenging times

Each Epiphany at Augustana we bless our church for the new year by marking the nave doorway with the initials of the three wise men traditionally known as Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar. But how much do we really know about these mysterious characters who appear in the second chapter of Matthew? In most Lutheran congregations, the wise men don’t figure very prominently when we think about Christmas. They may appear as distant silhouettes riding on camels behind a manger scene dominated by shepherds and angels. They are certainly eclipsed by Saint Nicholas as the patron of gift-giving, even though the Magi bear gifts for the Christ child already in the Bible.

We may also wonder how the wise men became associated with Christ’s manifestation on Epiphany celebrated annually on January 6. In the fourth century of the common era the Roman Church identified December 25 as Christmas, whereas previously January 6 was one of the dates associated with Christ’s birth. The tradition of counting 12 days of Christmas between these two dates, starting on December 25 with Christ’s birth and ending on January 6 with the adoration of the Magi, became a common practice since that time.

My interest in the Magi was stimulated by a recent family trip to Puerto Rico in March 2024. Even though it was not Christmas, we saw artwork there that prominently featured the three kings and accentuated their identification with the people of Puerto Rico. I learned that in the US Territory of Puerto Rico, as well as in Spain and other Spanish-speaking countries, January 6 is known as El Dia de los Tres Reyes Magos (Three Magi Kings Day). It continues to be an especially joyous festival, with family gatherings, gifts, singing, parades, and special foods. It was so important that before the Spanish-American war, after which Puerto became a US Territory, Three Magi Kings Day was observed as a national holiday.

Augustana member and emeritus LSTC faculty member José David Rodríguez wrote about the importance of the three kings in Puerto Rico in his book about Caribbean Lutherans: The History of the Church in Puerto Rico. He was not available to join us for Adult Forum because he was scheduled to be in Puerto Rico for El Dia de los Tres Reyes Magos, along with the ELCA Bishops who are meeting there!

Three Kings in Puerto Rico

In the 14th century work History of the Three Kings, the cleric John of Hildesheim states that the Kings hail from “Ind, Chaldea, and Persia,” referring to India, Babylon (or present-day Iraq), and Iran. Still other accounts from around the same time assert that each King traveled from a different part of the world, specifically from Europe, Africa, and Asia. These continents correspond to the three sons of Noah in Genesis, representing all the world’s nations, which is an emphasis at the end of the Gospel of Matthew.

In Puerto Rico as well as in other parts of Latin America, the three kings also represent different ethnic groups, but the emphasis is on the composite indigenous, African, and European ancestry of the people themselves. In Puerto Rico this interpretation developed in the 19th century and was emphasized in the 1950’s, serving as a symbol for the ideal of egalitarian democracy. In Puerto Rico slavery was abolished in 1873, after enslaved Africans participated in 1868 Grito de Lares revolt against Spanish rule. Slave owners were compensated and enslaved Africans were required to work an additional three years until 1876. Voting rights were granted five years after the 1873 “emancipation” in 1878. Changing roles and relationships among the citizenry required a new way of thinking about Puerto Rican identity.

A popular representation of the three kings is through the work of Santeros (woodcarvers of small saint figures), such as in the Santos de Palo (wooden saints) carving above entitled, “Los Tres Reyes Magos,” created by Juan Cartagena, Puerto Rico, 19th century. It is now in the Vidal Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

The three kings are mounted on Arabian horses of the kind that were used in Spain and brought to the New World by the Spanish (not camels as in some traditional depictions). Together they represent the indigenous Taino, African, and European ancestry of Puerto Rico.

The black king known in Puerto Rico as Melchior (“My King Is Light”) is in center, which is a position of prominence and leadership. In Spain, Melchior was of Moorish or North African origin, related to Spain’s being under Moorish rule for 800 years. In Puerto Rico, however, Melchior is dark brown and so represents Africa more generally. Melchior’s feast day in the Catholic Church is January 7. (Note that in European tradition the black wise man hailing from Ethiopia as a cradle of Christianity is often identified as Balthasar. Melchior in the European context is most often the old white-haired king commonly depicted kneeling to adore the baby.)

Caspar (or Gaspar), flanking Melchior to the left in this Santos de Palo, is traditionally of Asian origin. In Puerto Rico we see that he has the bronze complexion of the native Taino Indians. His feast day in the Catholic Church is January 6.

In Puerto Rico, Balthasar on the right represents a king from the West, specifically the dominating Spanish presence from the late 15th century. (In Europe by contrast, Baltasar hails from Iran or Persia, or is depicted as a young black man from Ethiopia.) His feast day is January 8.

As for their gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, these symbolize the gifts of charity, hope, and faith. They are given with no expectation of reciprocity or exchange. Gold as the most precious gift is given by Melchior who shows himself to be the most generous king. The gift of gold recognizes Jesus as an earthly king. It also finances the holy family’s flight to Egypt to escape Herod’s murderous plot, so Melchior provides a model for donating resources in support of refugees and asylum seekers. The frankincense given by Gaspar was associated with religious rituals and so symbolized Christ’s divinity. Myrrh given by Balthasar (in Puerto Rico the European, although in other versions of the legend myrrh is associated with the wise man of African descent, since myrrh was thought to be from Ethiopia) represents healing. It was said that if the baby reached out to receive the gift of myrrh, he would become a great healer, as indeed it turned out to be the case with Jesus. In other Christian strands of tradition, myrrh is associated with Jesus’ embalming at death, but in Puerto Rico the emphasis is on restoration of life and healing.

Crowns on the magi as in this Santos de Palo are relatively late in the history of art, appearing first in the 10th century. Already in the 5th century, however, the magi were identified as kings. This understanding is based on the interpretation of passages such as Ps 72:10-15 that refer to foreign kings bringing gifts to God’s own righteous king.

Wooden Santos de Palo carvings are still being made by Santeros to this day and may be purchased on Amazon, which is where this set above was advertised. You can detect many of the conventions of the previous 19th century Santos do Palo carving repeated in this simpler, contemporary version.

El Dia de los Reyes Magos is enacted in Puerto Rico with parades and public appearances of the kings, as seen in this photo advertising the festival scheduled for January 6, 2025 in the southern Puerto Rican city of Juana Diaz. Note the ethnic diversity of the kings dressed in elaborate, festive costumes.

Los Reyes Magos are a symbol of the Puerto Rican people, as seen in this yard banner featuring the three kings with the flag of Puerto Rico.

In March 2024 our family visited the Seminario Evangélico de Puerto Rico, where several LSTC alumni have taught and served as administrators over the years. These include the father of Dr. José David Rodríguez and José David himself. LSTC continues to have a close association with SEPR, including a cross-registration agreement.

At the Seminario Evangelico de Puerto Rico, Doctora Lydia Hernandez Marcial, LSTC alumna and professor of Old Testament, poses with pride beside a colorful piece of art in her office depicting los Reyes Magos worshipping the sleeping Christ child.

Closer to home, El Dia de Los Reyes Magos has also become part of the Chicago scene. Festivities have been held in Humbolt Park for more than 25 years. Here the Magi Kings are involved in distributing gifts to children.

Augustana has raised up our own Three Kings. Here Erik Erling, Elijah Tammen, and Danny Tammen follow yonder star in pre-pandemic January 2020.

Leading the Augustana congregation, the three kings bow to worship and adore Christ.

The Magi in Early Christian Art

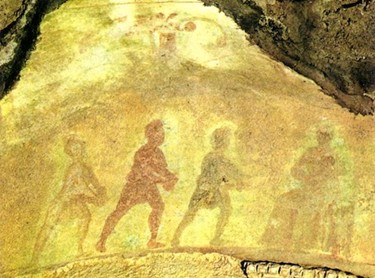

The earliest depiction of the Adoration of the Magi is from the 3rd Century (200-250 CE), found in the Catacomb of Pricilla in Rome, over the archway of the entrance to the Greek chapel. Silhouettes of three figures of approximately the same size with different colored clothing stride forward bearing gifts intended for Jesus, in the lap of a seated Mary. This fresco is also one of the earliest depictions of Mary holding Jesus.

Another very early depiction of Mary holding Jesus from the 3rd century is also found in the Catacomb of Pricilla, Rome. To the left, a prophet (Balaam or possibly Isaiah) points to the star that the wise men will follow. The allusion is most likely to Num 24:17, where the non-Israelite prophet Balaam proclaims, “a star shall come forth out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel.”

Adoration of the Magi, on a 4th Century Sarcophagus from the Cemetery of St. Agnes in Rome, Museo Pio Christiano, Vatican, now includes camels, based on details provided in Isa 60:1-6: “…the wealth of the nations shall come to you. A multitude of camels shall cover you, the young camels of Midian and Ephah; all those from Seba shall come. They shall bring gold and frankincense, and shall proclaim the praise of the LORD” (Isa 60:3-6). The three Magi are youth of the same size and appearance, with the first pointing to the star above Mary and Jesus, who reaches out to receive a gift.

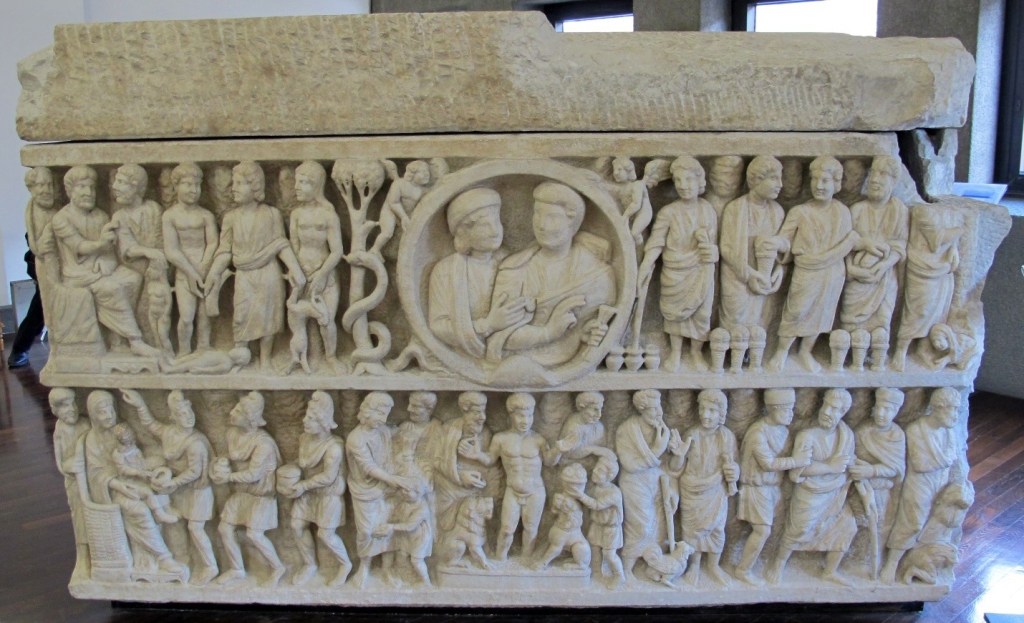

On the Dogmatic Sarcophagus from the 4th century, the Adoration of the Magi appears in the lower left corner, among other scenes from the Bible. (For example, the creation of Adam and Eve appears directly above the Adoration of the Magi and the baptism of Jesus appears in the lower center.)

This closeup of the Adoration of the Magi from the Dogmatic Sarcophagus, 4th century, Museo Pio Christiano Vatican, includes distinctive hats worn by the youth (known as Phrygian caps) as well as luxurious mantles, suggesting their status as international travelers from the east. The first wise man points up to three circles in the frame, showing the other wise men the place where we would expect the star. Joining this scene, Joseph views the events from behind Mary. The awed expressions of the Magi and their reverent approach of Christ are especially attractive details of this version.

This Funerary Plaque from the Catacomb of St. Pricilla shows a deceased woman on the left addressed with the words “Severa, in God you live.” To the right a stylized version of the Adoration of the Magi appears with many elements that we have seen previously, suggesting that the Magi recognize Christ as the divine source of eternal life in God.

Moving from the early funerary contexts of catacombs and sarcophagi, the Magi begin to appear on ornate walls of public buildings constructed with official sponsorship, as in this 6th century mosaic from the time of Emperor Justinian at Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna. Only the legs of the Magi with their colorful Persian pants and pointed shoes are original to the 6th century, marking these figures as wealthy international travelers from the East. All work above the waist (including the names prefaced by the abbreviation “SCS” meaning “Saint”) was reconstructed in 19th century. The red Phrygian hats reflect a convention already seen in the 4th century, but other details show later developments, including the wise men’s representation of three different ages of humanity (old age, youth, and middle age) and distinctive ethnic identities. To the right, the mosaic show their goal in following the star, seen in the picture below.

To the right of the Magi in the wall mosaic at Sant’ Apollinaire Nuovo, Ravena, we find a formalized depiction of Mary and Child seated on a throne, flanked by angels who appear ready to help with the presentation of the gifts

The Adoration of the Magi in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art

Moving to the late Middle Ages, this fresco of the Adoration of the Magi (1303-1305) from the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel in Padua, Italy was created by the Italian painter and architect from Florence, Giotto de Bondone (commonly known mononymously as “Giotto”). The camels from Isa 60:6 make their traditional appearance, with the camel in front expressing surprise and delight at what he sees, requiring the reassurance of a youthful handler. A new development emerges in depicting the Magi as representing three ages of humanity (old age, middle age, and youth). This fresco shows the convention of the elder white-haired Melchior kneeling first to adore the Christ child by kissing he feet after presenting his gift of gold (which the angel to the right seems to be helpfully holding). The middle aged, dark-bearded Balthasar, waiting for his turn in reverent reflection, was considered in some traditions to be from Babylonia or Persia because of the similarity of his name to some of the names found in the book of Daniel, set in Babylonia and Persia. The youthful Caspar completes the trio. Note that the Magi have crowns, indicating that by this time they have become Kings. The senior Magi has set aside his golden crown on the stone ground in acknowledgement of the newborn King. The Magi are clearly saints, indicated by the halos. In this depiction Joseph has fully joined Mary in presenting the Christ child to the Magi. The orange star looks like a comet in the brilliant blue sky, hurtling towards the holy family.

See what conventions and creative treatments you can discover in this Adoration of the Magi by the Italian painter Gentile da Fabriano, completed in 1423. This painting is housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy, and it is considered Gentile da Fariano’s finest work. Wikipedia quotes an art critic who ecstatically describes this painting as “the culminating work of international Gothic painting.”

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi, from 1475, features members of the Medici family among the cast of well-dressed characters, most of whom seem more interested in conversing amongst themselves than adoring the Christ child. The oldest wise man kneeling to adore Christ by dandling his feet respectfully covered by a cloth, is Cosimo De’ Medici himself, head of the wealthy Medici family and of the Medici Bank. It seems appropriate that his gift was gold! The other two Magi appear to be his sons or possibly other relatives, in consultation or dispute with each other as they wait for their turn to present their gifts. All halos have disappeared. Joseph appears to be nodding off to receive the dream vision to flee with his family to Egypt for safety. The ruins of the stable and of the surrounding grand arches suggest decadence and decline, even in the presence of such luxury. The man on the far right looking at the viewer is the painter Botticelli himself. The patron of the painting, Gaspare di Zanobi del Lama (1411-1481), was a businessman who founded a chapel in the Church of Santa Maria Novella dedicated to the Magi and the Epiphany, where this painting was located before passing into the hands of the Medici family. It has been housed in the Uffizi Museum in Florence, Italy since 1796.

Hieronymus Bosch, Adoration of the Magi, 1485-1500, Netherlands, has much reduced the cast of characters in his presentation of the scene in the form of a triptych. Shepherds lurk about the back of the collapsing stable and on its roof, as the dignified Magi take central stage. Bosch portrays the Magi as having different ethnic backgrounds. The elder wise man kneels in adoration, as the other two look on reverently. Mary and the child remain set apart and aloof, and Joseph is nowhere to be found. The mad king in the doorway of the stable is a remarkably strange addition. Is this a portrayal of the raging Herod or more generally of royal insanity? While the Adoration of the Magi unfolds in the front, ordinary life in the country and the more distant city continues uninterrupted. The sides of this triptych represent the sponsors of this painting who join the Magi in adoring the Christ child.

The enormous Adoration of the Magi (1609-1629) by Rubens (355.5 cm/11.6 ft x 493 cm/16.1 ft), housed in the El Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain, develops many of the conventions associated with the scene in distinctive ways, using extreme contrasts of light and darkness.

The Roman Catholic Cathedral at Cologne, Germany houses a golden reliquary shrine that according to tradition contains the bones and clothing of the three kings. According to legend their relics were identified by Queen Helene and moved to Milan by her son Constantine for safe keeping. After Emperor Frederick Barbarossa conquered Milan, the relics were brought to Cologne in 1164 as a gift. The Cologne Cathedral was constructed to provide a fitting site for these relics over a period of seven centuries, starting in 1248 and continuing to 1560, and then after a long hiatus again from 1814 to completion in 1880. The Cologne Cathedral is the largest Gothic church in northern Europe, with twin towers standing 515 feet (157 meters) tall. It remains the most visited site in Germany today. It survived 14 bombings during World War II and was severely damaged, but the structure survived above the otherwise destroyed city and has since been rebuilt. Isn’t it odd that the wise men traveled following a star to see the Christ child and now millions travel from far and wide to see the shrine that contains their bones?

The golden reliquary Shrine of the Magi was created between 1190 and 1220 by Nicholas of Verdun in the shape of a basilica, to house the bones of the Three Kings. Now located in the Cologne Cathedral, it is the largest and most magnificent of all existing medieval reliquary shrines. The front features the theme of the Magi presenting their gifts on the lower left. Christ’s baptism, an event also associated with Epiphany, appears opposite on the lower right. At the top, Christ in Majesty appears between angels holding the instruments of his Passion.

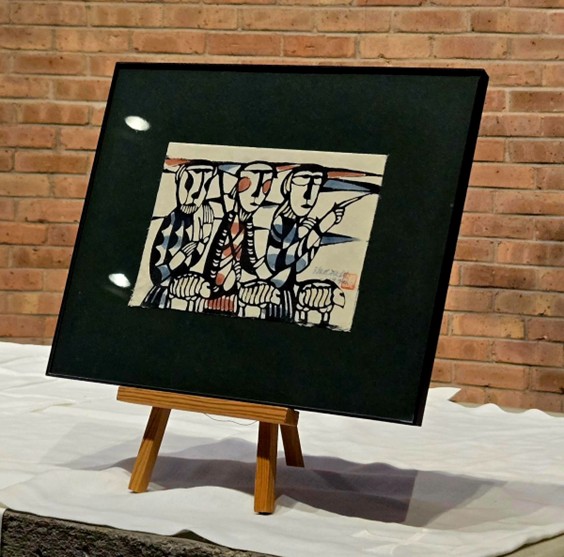

Adoration of the Magi in Ethiopian and Japanese Art

Art from other parts of the world depicts the Adoration of the Magi without many of the conventions accruing over time in Europe. It is interesting to consider examples from Ethiopia and Japan as contrasts to the previous representations of the scene.

Reflections on the Magi for Our Times

The Magi of long ago offer insights and practices for how we can live faithfully as Christians in our disturbing and challenging times.

- They sought a like-minded community. Whether there were two, three, four, or twelve Magi (the early interpretations of the biblical story vary in this detail, although in art the convention from earliest times has been three), they did not act alone but journeyed together as companions, sharing challenges, discernments, and commitments. We can continue to build such a community at Augustana.

- They remained open to learning new things and continually sought out additional information and perspectives from a variety of sources. They looked for insight from nature (the star), crossed borders and cultural lines to approach an unfamiliar urban center (Jerusalem), asked advice and directions from the highest levels of government (Herod and all of Jerusalem), listened to religious leaders (priests) and teachers (scribes), gleaned knowledge from sacred Scripture (Micah 5:2), and took seriously the warning that came in a dream. Where will our ongoing education at Augustana about things that really matter take our community?

- They were not content merely to take in information and become even wiser, but they took action based on what they had to offer (their gifts and adoration) and what they were learning along the way. They didn’t wait to have a perfect plan, they just set off following the star, modifying their course along the way as things became clearer. They came from the east traveling in darkness over unfamiliar terrain, arriving at Jerusalem then moving on to Bethlehem to the very place where the star showed them the child with Mary his mother, then home by another route to protect life. How will our efforts at Augustana continue to evolve in response to the needs that we discern through following Christ?

- They also seemed to have fun, bringing their best gifts and rejoicing exceedingly with great joy when they saw the star pointing the way to worship and bow down before the Christ child (Matt 2:10-11). The Magi continue to symbols of Christian enjoyment during the season of Christ’s birth wherever El Día de los Tres Reyes Magos is observed. We at Augustana can continue to join this celebration.

- Through it all, they sought the Christ child. Martin Luther explained what it means to seek and find Christ in a sermon he delivered at Epiphany in 1527, almost 500 years ago:

- “Let us observe how these Wise Men took no offense at the mean state of the Babe and his parents that we also may not be offended in the mean state of our neighbor but rather see Christ in him, since the kingdom of Christ is to be found among the lowly and despised, in persecution, misery and the holy cross… Those who seek Christ anywhere else find him not. The Wise Men discovered him not at Herod’s court, nor with the high priests, nor in the great city of Jerusalem, but in Bethlehem, in the stable, with lowly folk, with Mary and Joseph. In a word, they found him where one could least expect it.” (From Martin Luther, “The Gospel for the Festival of the Epiphany: Matthew 2:1-12” (1527), quoted in José David Rodríguez, Caribbean Lutherans, p. 79.)

Resources for Further Exploration

Robin M. Jensen, “Witnessing the Divine: The Magi in Art and Literature,” Biblical Archaeology Society, December 2001

https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/witnessing-the-divine/

El Museo de Barrios, “Three Kings Day Multicultural Connections: Educator Resource Guide”

https://www.elmuseo.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023_3KD-Educator-Resource-Guide-.pdf

José David Rodríguez, Caribbean Lutherans: The History of the Church in Puerto Rico (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2024), especially “Chapter 3: Lutherans Begin Their Mission in Puerto Rico,” pp. 69-87, and the first pages of “Chapter 7: Findings,” pp. 175-179 which recounts a disastrous attempt to introduce Santa Claus into a Puerto Rico school celebration of El Dia de los Tres Reyes Magos.

You must be logged in to post a comment.